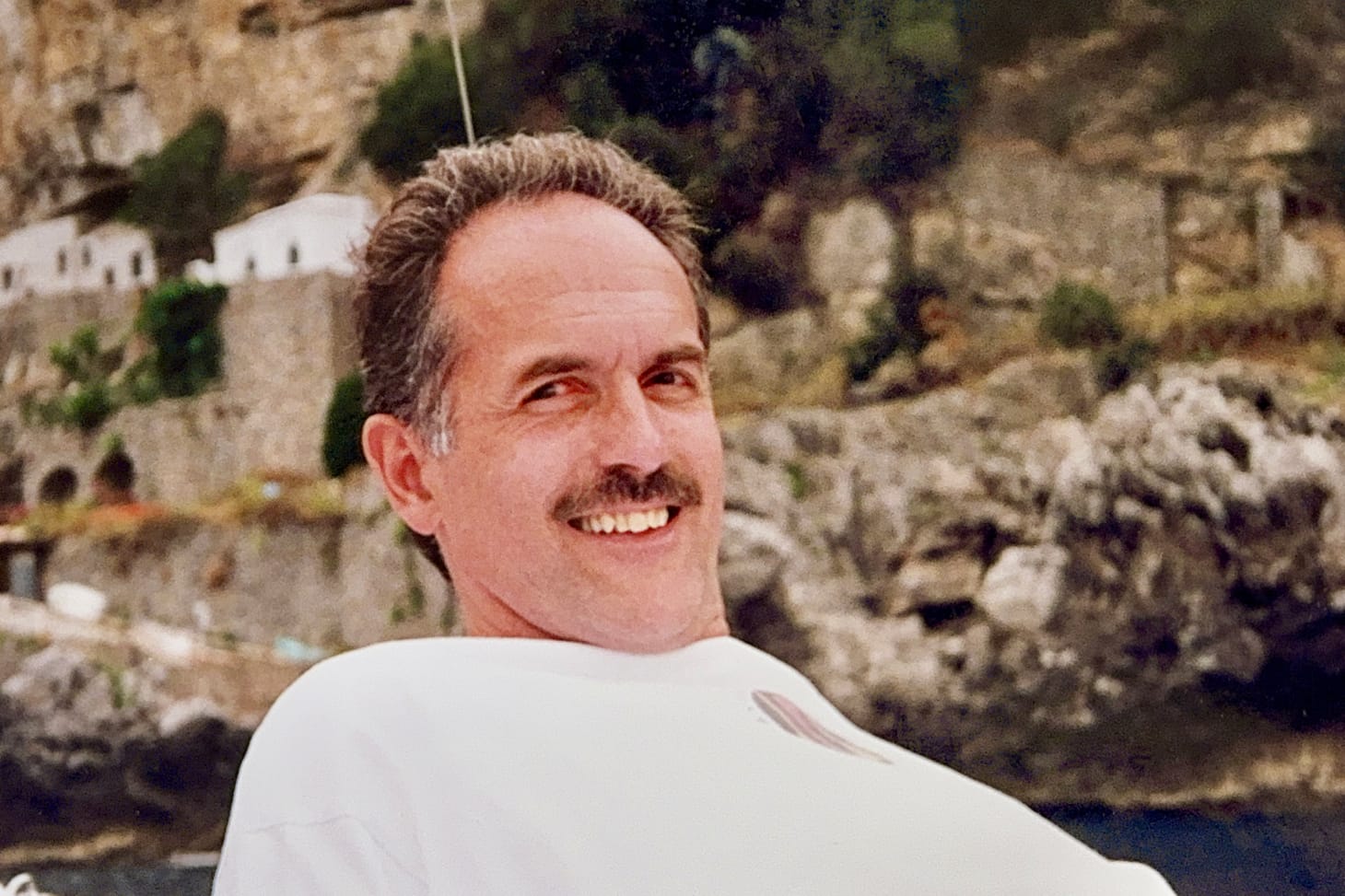

Stephen Clark Seward

My eulogy for Dad

My dad died last week. My mom, his siblings, and I were at his side. I am still coming to grips with the loss, but managed in the last few days to write an obituary for his favorite local paper and a eulogy for his funeral, which I'm sharing below. You can also view a recording of the service, which was held on June 17, 2024, at B'nai Israel synagogue in Southbury, Connecticut. I love you, Dad.

Thank you all so much for coming. It means a lot to me and my mom and would mean a lot to Dad, too. He cared about making an impact, and you are all testament to the impact he had on so many lives.

I’m Zach Seward, Steve’s son, but I’m guessing the forehead already gave that away. Today I want to share a few scenes from Dad’s life, many of which I was there to witness, some I came to know well from detailed descriptions in long letters he would write to me.

§

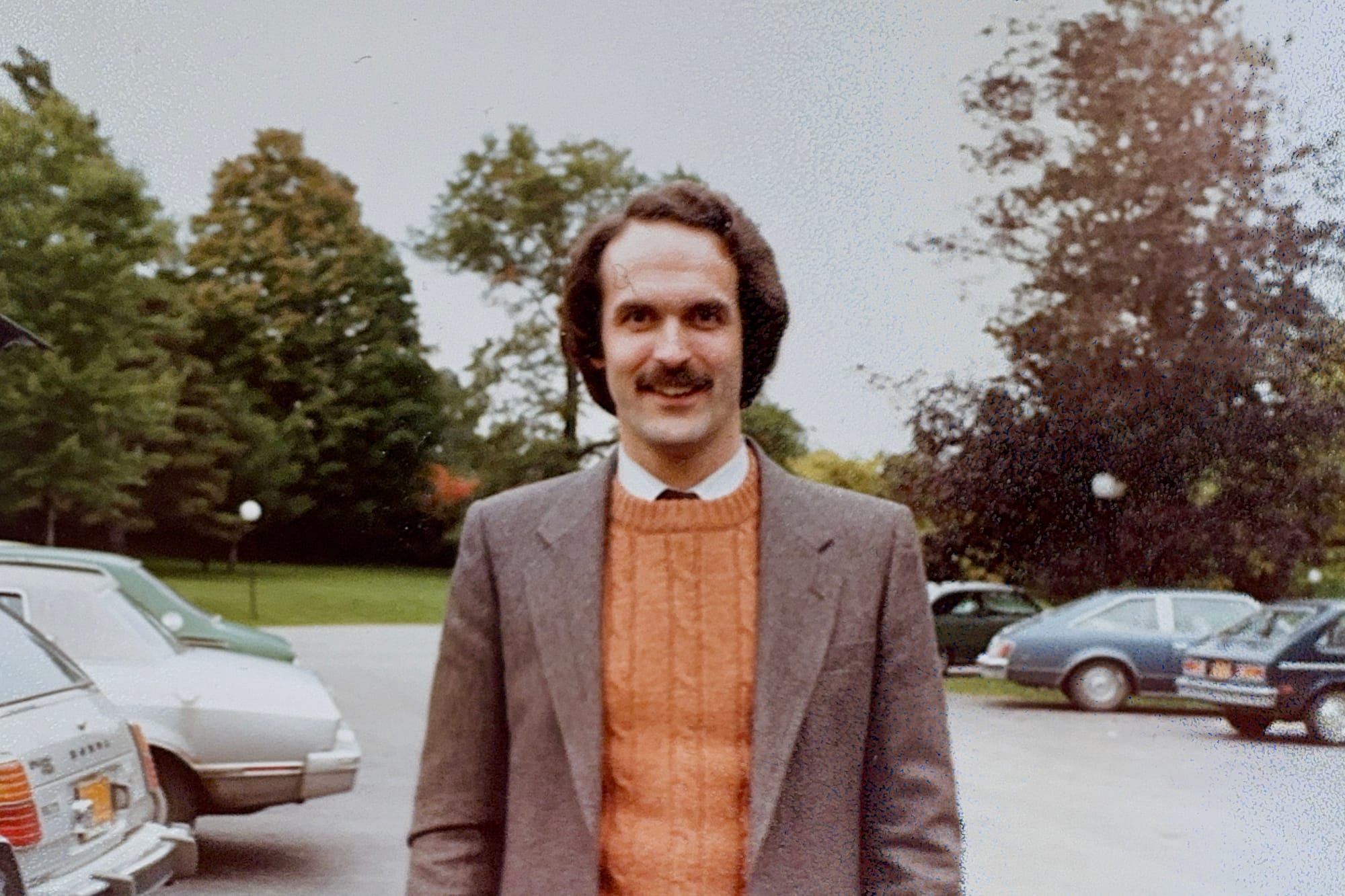

It’s the early 1970s, New York City. My dad, sporting a three-foot mop of hair and a goatee to match, sits in the newsroom of The Guardian, where he got a part-time job out of college helping lay out the paper. (To be clear, this wasn’t the Manchester Guardian, a liberal paper in its own right. This was a radical, American weekly that would have considered that other Guardian to be hopelessly bourgeois, while debating the finer points of Trotsky vs. Mao.) Next to Dad are some personal items. One is a cutout quote, the epigraph of an Irving Howe essay collection, that resonated with Dad so much that he pinned it to the wall. It reads:

Once in Chelm, the mythical village of the East European Jews, a man was appointed to sit at the village gate and wait for the coming of the Messiah. He complained to the village elders that his pay was too low. “You are right,” they said to him, “the pay is low. But consider: the work is steady.”

This was kind of my dad’s creed. No one is coming to save us. There are no easy answers. We will never get it right. And eventually we’ll die. All that matters is what we choose to do while we’re here.

§

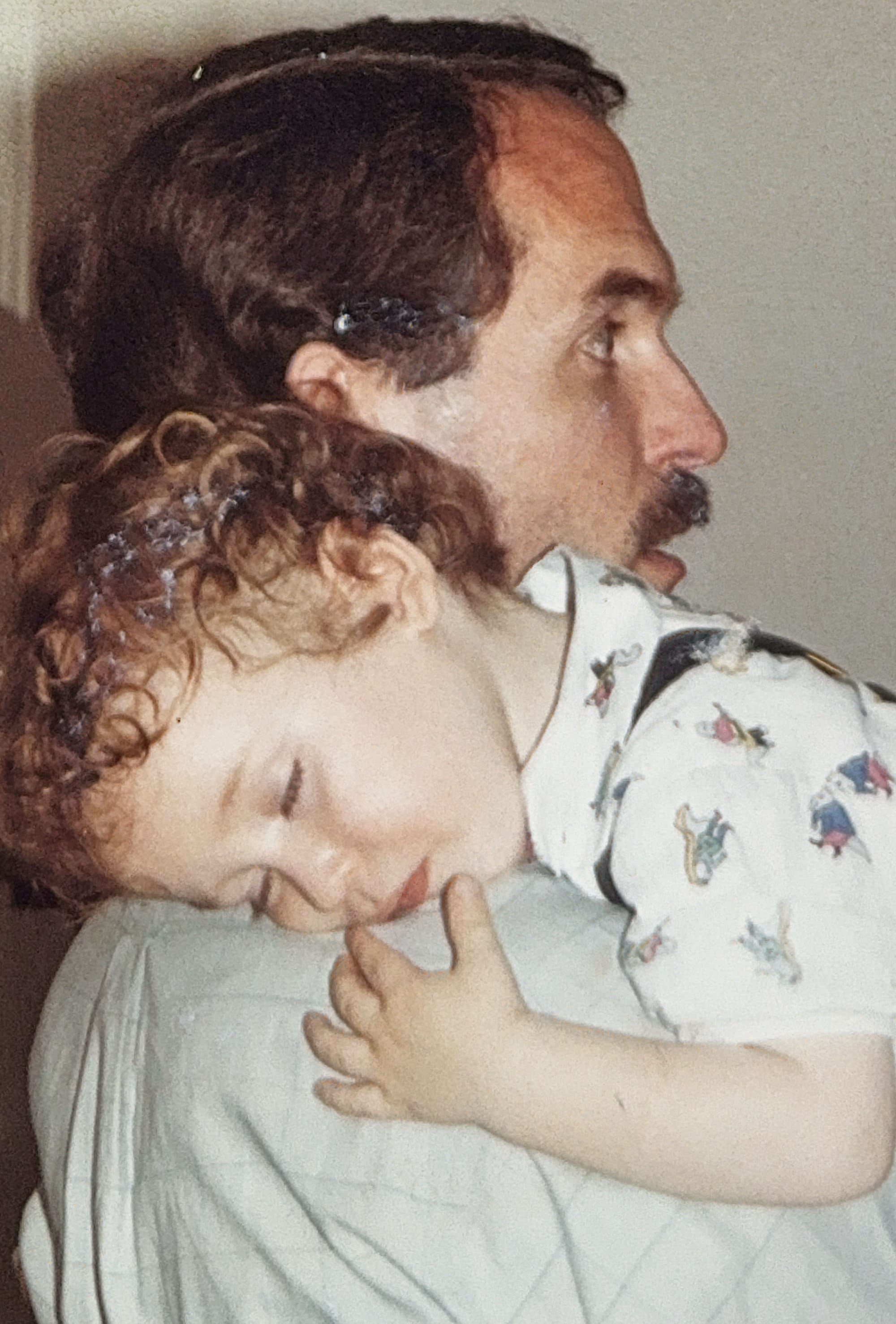

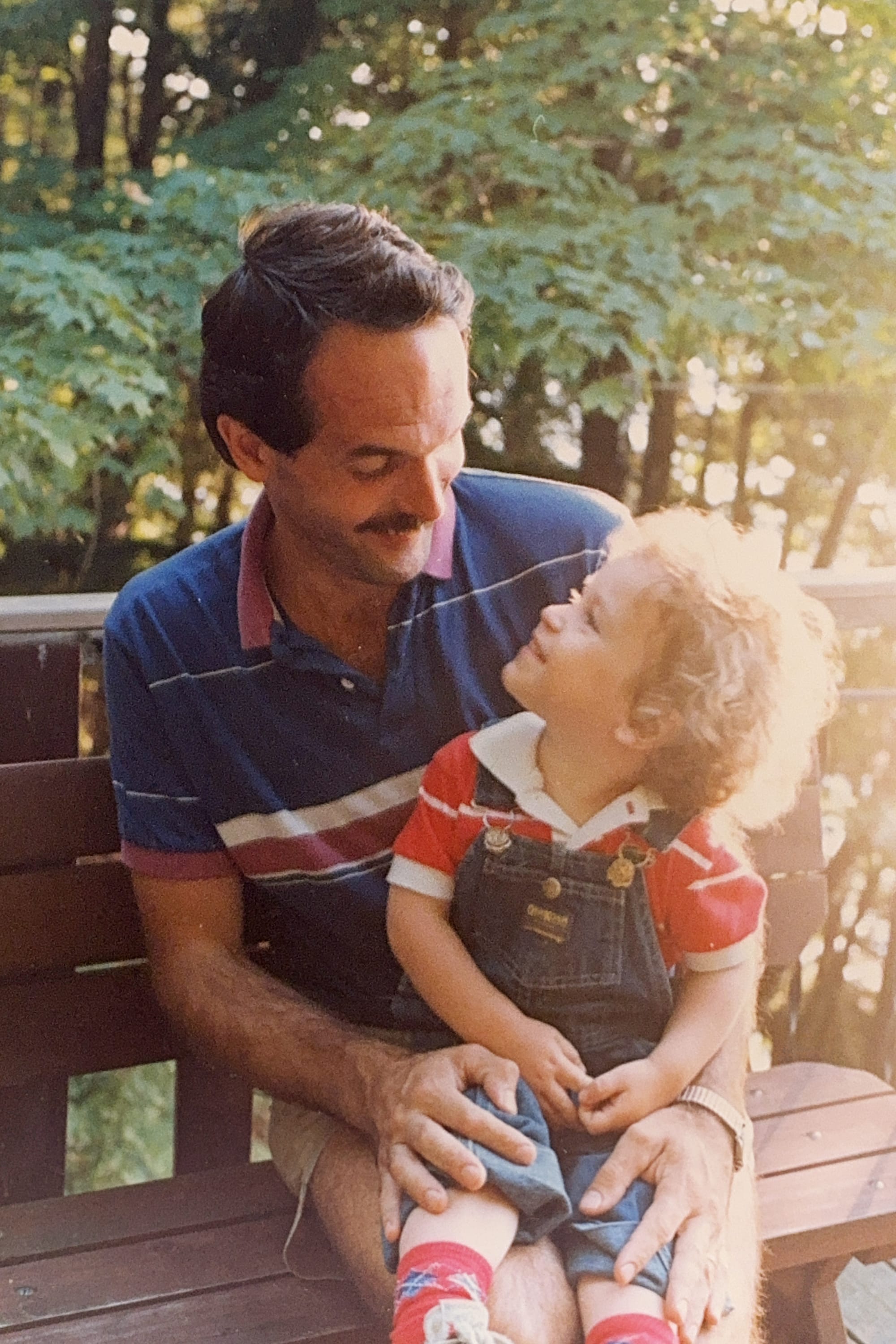

It’s dinnertime, and Dad is there. He's always there. Not a lot of parents in Scarsdale made it home from their jobs in Manhattan in time for dinner, but he did. He made a point of telling me it was unusual, too.

I probably rolled my eyes when he said that. I couldn’t have known what dedication it took, or what an impression it made on me, until I found myself with two kids of my own, checking my watch at the office, and feeling like it’s time to get home. Dad didn’t make a point about being home for dinner to get brownie points. He wanted me to know it was important to him and should matter to me, too.

At the dinner table, I was outnumbered two-to-one, so talk often turned to Mom and Dad’s jobs. Those conversations were lessons, too — about reading a 990 non-profit tax return and the merits of the minimum distribution requirement for foundations, but also about meaningful work, advocating for a cause, and treating people with respect. I learned a lot about what was important to Dad by what he chose to talk about.

Dad reveled in his relationships with everyone, it didn’t matter who they were. At dinner, I got more details about the support staff at work than about his boss. Dad would go on about the lobby security guard, and also the security guard’s daughter, the security guard’s upcoming dental appointment, and a new phrase the security guard taught him in Spanish.

I definitely rolled my eyes at that like, great, Dad, you befriended the security guard, felicidades. Now I understand he was not bragging but making sure I understood that everyone is important, everyone has a story, and everyone is deserving of our attention. I imagine a whole lot of people are here today because Dad, in one way or another, made clear that he cared about you and your story.

§

It’s a recent weekend, and I pull a book down off the shelf. Papers fall out and down to the floor. Oh right, this is one of Dad’s books, and Dad’s habit is to stuff the jackets of his books with relevant newspaper clippings, maybe The Times review or a profile of the author or just something he found related. His copy of Underworld is as thick with clippings about Bobby Thompson’s home run as the 800-page book itself. That’s how Dad made books come alive and stay with him his whole life.

§

It’s the spring of 1970, approaching college graduation, but my dad is nowhere near campus. He’s driving across the Canadian border with another anti-war organizer and a deserter from the Navy who enlisted their help escaping the U.S. after walking off his base. As they drive, a Montreal radio station is playing all of Bob Dylan’s albums in order. “By the time we heard John Wesley Harding,” Dad wrote later, “we were crossing the St. Lawrence River and entering the city of Montreal.”

Dad’s typewritten essay about the mission, which he gave me last year, has some dramatic moments, but what’s striking is how much he dwells on the story of the deserter, whom he calls Kevin. To my dad, Vietnam was not just about Western imperialism, Cold War proxy fights, and Richard Nixon. It was a personal tragedy. He wrote:

[Kevin] didn’t have a “political position” on the war itself, he wasn’t a member of any movement. Kevin was 18 years old, and he felt very much alone. What he did know was that he didn’t like military discipline any more than he relished the prospect of patrolling some unknown Vietnamese river.

The first time I ever saw my dad cry was on a visit to the Vietnam Memorial. He looked up a high-school classmate: low draft number, no college. We rubbed the name. The wall unfurled in front of us. Though he didn't say it, I have to imagine Dad also thought of Kevin in that moment and was grateful that, for all the tens of thousands of names on the wall, at least one was missing.

§

It’s a weekend afternoon in the ‘90s, the second time I see my dad cry. We’re watching Field of Dreams, and Ray is playing catch with a younger version of his dad. I think a lot of fathers and sons have shared tears over that scene, but I couldn’t have understood what my dad was really thinking, what it’s like to watch when your dad is no longer here.

His dad, Grandpa Ross, would take him to a Yankee game every year on his birthday. Dad always chose a doubleheader, to stretch out the day as long as he could and move closer to the field for the second game. When Dad would take me to the stadium, he taught me how to score, how to sneak into better seats, how to notice details on the field that you can’t see on TV, and how to weave through the South Bronx while everyone pours into the streets celebrating the 1996 World Series. We were there.

§

It’s 2010, and I’m in my 20s, finally living in the city like Dad. Randomly, I’m introduced to an old girlfriend of Dad’s from college. They’ve lost touch, so I catch her up on Dad’s life. She stops me, “Steve Seward moved to Scarsdale?!” And, yes, if you only knew Dad in the late ‘60s, it would seem ironic. I said something nice, but what I wanted to tell her is that of course he moved to Scarsdale. Dad and Mom spent every last dollar they had to move wherever I would get the best education. I think even teenage radical Stephen would understand that decision.

§

It’s vacation, somewhere upstate. Dad buys the local newspaper to get a sense of the place. He did that everywhere we went, always curious about the world around him. We’re in a restaurant, and he proposes his favorite game, which is to guess the stories of people at the neighboring tables. He likes to remind me that everyone has an interesting life if you are willing to get to know it. He’s always looking around and encouraging me to do the same. Noticing was how he paid respect.

§

It’s Friday night at 10. We’re on the couch together eating ice cream and watching Homicide: Life on the Street, a gritty procedural about murder detectives in Baltimore. I am 10 years old. How Dad has convinced Mom to let me watch this show at this age, I have no idea.

Dad appreciated great writing, and Homicide at the time was the peak of the form, so he wanted me to appreciate it, too. He also got HBO to watch The Sopranos and plenty of other shows I probably shouldn’t have been watching. Dad loved great characters with interesting stories.

§

It’s the pandemic, and my parents are having the time of their lives as full-time caregivers to my son Hugo. It’s also my birthday, and my dad’s tradition is to write me a letter on the occasion. His missives could run a dozen pages or longer, often tucked into a book he wanted me to read. That year’s letter was relatively short at 3,000 words. He wrote:

Sometimes being with Hugo also puts me in mind of my father. Maybe one reason these birthday missives have become an annual rite is that I am often finishing them around Father’s Day. My father was an inspiration to me and a great man in so many important ways, while also burdened beyond understanding. I find grandparenting creates many new dynamics, but one important one is a new appreciation for generations. And I’m not thinking simply about the stuff of family themes and quirks, or similarities and differences. No, I’m thinking more about tradition and grounding (how we are unwittingly so like our parents) and about evolution and change (how we also make choices to be different, while building on what we know). As Hugo grows, he too will make those choices and leave you feeling all those positive emotions. But I think it’s not easy to appreciate all that while you are still so immersed.

Dad told me the other day that he was not afraid to die, that he felt it was time, and that he was at peace with the whole process — which I found remarkable because Mom and I were still just reeling from his terminal diagnosis, let alone processing it. Dad, however, was characteristically contemplative about death.

He had only one regret, he told me, about what was happening. Always fascinated by other people, he was sad not to know what his grandchildren Hugo, and now Nicholas, will become, what their stories will be.

§

It’s March 2003, American troops are amassing on the border of Kuwait to invade Iraq. I’m a high-school senior who’s fiercely opposed to the war. Dad takes me to our first protest together, in Times Square.

§

It’s July 1, 2004. I’m in the hospital, just out of surgery. Dad is by my side, he has brought me dinner so I don’t have to eat the hospital food, and the Yankee game is on the television dangling from the ceiling. It turns out to be the game in which Derek Jeter makes that famous dive into the stands to catch a foul ball and the Yankees beat the Red Sox in 13 innings.

But we never see The Dive. We spend the whole evening, instead, talking about life. Dad has the same disease — Crohn’s — that put me in the hospital. He had the same surgery, too, when he was younger. I can only imagine what he felt sitting by my side that night, but let me tell you, the surgery was worth it for the conversation alone.

§

It’s The Head of the Charles 2022, the famous regatta in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dad is rowing with a quad in a boat named Resilience. At 74, he’s not quite the oldest rower out there, but he’s close. Mom is cheering from the bank of the Charles River. Dad was not one for bucket lists, but this race feels very much like crossing off an important item.

Dad’s favorite part of rowing was that feeling, he once described to me, of being in total sync and focus with your skullmates, cutting still water with your oars, and losing your sense of self to the collective of the boat

§

It’s Father’s Day, and Dad sends me a George Saunders quote:

Before we had our kids, I was a decent person, kind of habitually, but nothing felt morally urgent. Then the kids came, and everything suddenly mattered. The world had a moral charge. If I love these guys so much, it stands to reason that every other person in the world has somebody who loves them just as much—or they should have someone who loves them as much. The world was full of consequence.

That which helps what you love is good, that which hurts it is bad, and even a small hurt is significant. You see somebody come into the world, tiny and brand new and blameless, and you’re like, That person deserves the best. So, by implication, everybody deserves the best.

§

It’s a hot summer night in 1998, and I’ve just finished a Little League game. Dad is the coach, I’m the catcher (which was Dad’s position, too). We lost, but we can both tell it hardly matters. I’ve been sick a lot lately — Crohn’s again — and just getting through the game is a victory. Dad proposes that we go to Nathan’s to celebrate, and we sit talking about the game, how I’m feeling, strategies for coping with the pain, President Clinton’s impeachment, and whatever else was going on those days. Those were the most important hot dogs of my life.

§

It’s the 1950s, and Dad is at Idlewild Airport to greet his father, my Grandpa Ross, who’s returning from a two-month-long business trip in Asia. Stevie, as everyone called him then, is running around the gate and yelling, “My daddy is coming, my daddy is coming.”

And then, in the ‘60s, Grandpa Ross decides to give it up for the cloth, becoming a Presbyterian minister in upstate New York. It’s a dramatic change for the whole family. Dad enjoys reading and debating his dad’s sermons — the son of a preacher man. Dad isn’t religious, exactly, but he develops strong opinions about religion. For him — and for Grandpa Ross, who later left the clergy and became a Quaker leader — the specific liturgy or denomination was not the point so much as the fundamental values of human dignity and respect that underlie all faiths.

§

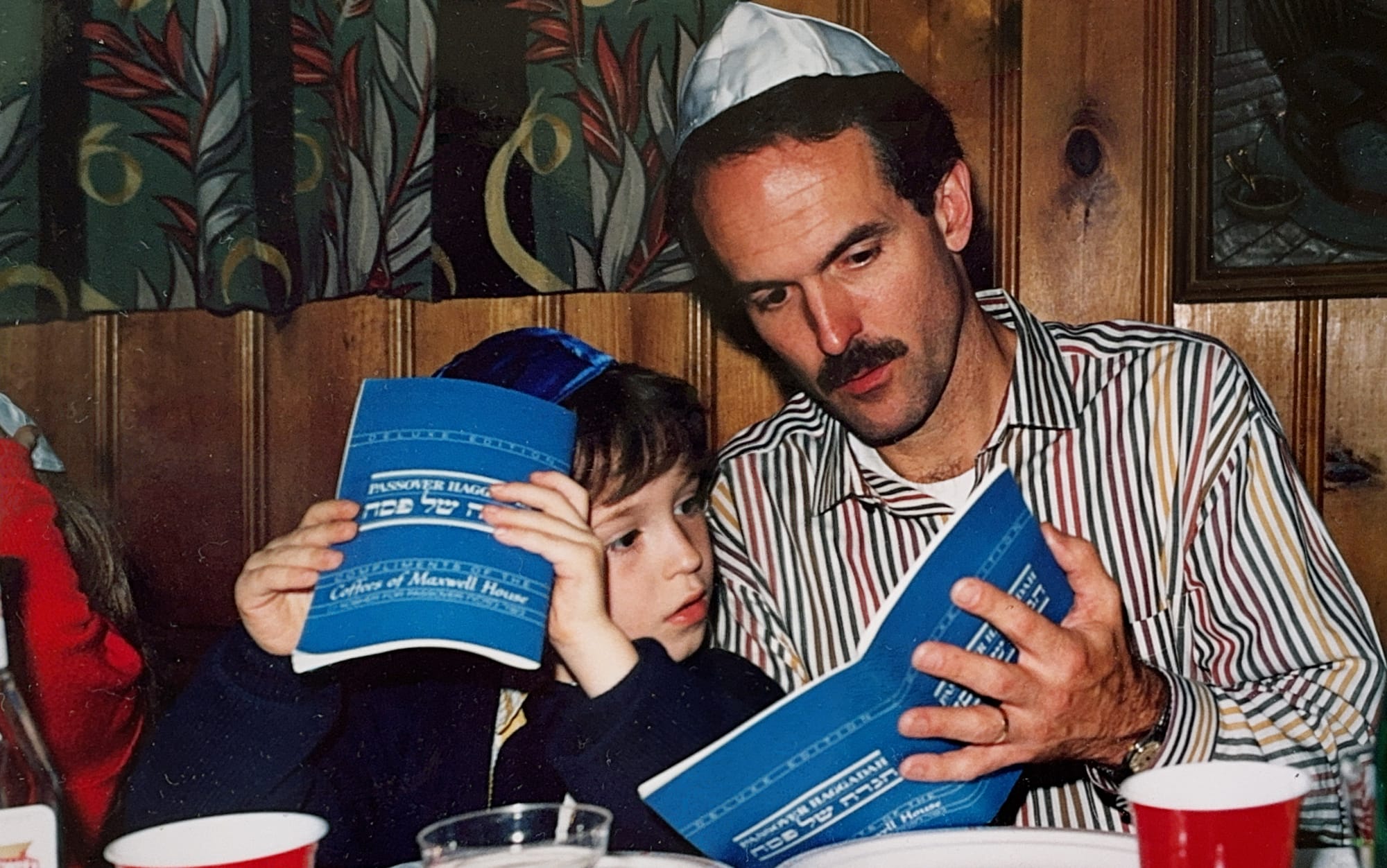

It’s Rosh Hashanah, and Dad is hurrying us out the door because he wants to make sure we get good seats. He was the most Jewish goy I ever met. Dad loved the music, knew his Old Testament, and of course felt at home in a place of worship (especially one with stained-glass windows like our Reform synagogue had). My parents would go to Shabbat services on random Fridays. Dad always paid special attention to the sermon, and would pick apart the rabbi’s argument on the ride home.

Dad never really picked a faith for himself. I think, if forced to choose, he would call himself a Humanist or maybe just a Democratic Socialist. But he embraced Mom’s Judaism and participated eagerly in my own religious upbringing. He also happened to be good friends with the local rabbi here in Connecticut, because of course he was. So that is how a Christian named Seward ended up lying here in temple and resting for eternity in a Jewish cemetery.

Actually, it was for a long time my dad’s wish that he be cremated, which is the tradition on his side of the family. He felt strongly about it and would often remind us how Grandpa Ross felt that funeral homes and many death rituals were a boondoggle. If you knew my dad, you can easily picture him making the argument, channeling his own dad’s moral outrage about the death industrial complex. But in the last few months, as it became clear he wouldn’t survive cancer, Dad’s view softened. None of the principles at stake were nearly as important to him as his love for Mom. He wanted to be buried with her and found a beautiful, old cemetery in Morris that accepts non-Jews. They went to visit the spot a few weeks ago together.

Every big decision Dad made in his life seemed well considered and felt to me like a teaching, this choice perhaps most of all. Not enough time has passed for me to fully process the lesson, but here’s what I’m thinking about it so far: Dad cared a lot about a lot of things. He didn’t know how to hold a view any way but strongly, and he taught me to be the same way. If you’re going to care, you might as well care a lot.

Yet all of Dad’s views about death and burial fell away when he considered what was most important to him: the people he loved, being with Mom, being at peace near Bantam Lake. I think he would want me to know that that’s the stuff of life, and what you do while you’re here is a hell of a lot more important than where you end up in the end.

§

It’s June 17, 2024, the day of Dad’s funeral. He long ago taught me how to knot a tie, but he was always the one with a set of backup collar stays, which of course I forgot. That’s my job now, I guess.

In the last few weeks, I’ve been listening to a lot of Phil Ochs, who was Dad’s favorite musician. I've had one song, in particular, on repeat. It’s not about politics or the war or other important topics to my dad, but about something even more crucial to him: what you do with the time you’ve got.

Thanks to Dad's cousin John Coghill, who sang "When I'm Gone" at the funeral. Dad worked in non-profit fundraising his whole life and would be honored by a donation in his name to any charity, particularly favorites of his like Educate! in East Africa and the Litchfield Hills Rowing Club.

Read more from Zach

Sign up to receive occasional emails with new posts.