AI is not like you and me

My talk at an Aspen Institute event

I just gave this lightning talk at "AI & News: Charting the Course," a one-day event hosted by Aspen Digital, an arm of the Aspen Institute, at the Ford Foundation's headquarters in New York. The event brought together a lot of media executives along with folks like myself who are working on applying AI to journalism. I took it as an opportunity to get something off my chest. The event was held under Chatham House rules, which is sort of like British for on-background, but of course I'm free to make my own comments public. And, to be clear, as with everything else I publish here, these are just comments, not some official position of my employer.

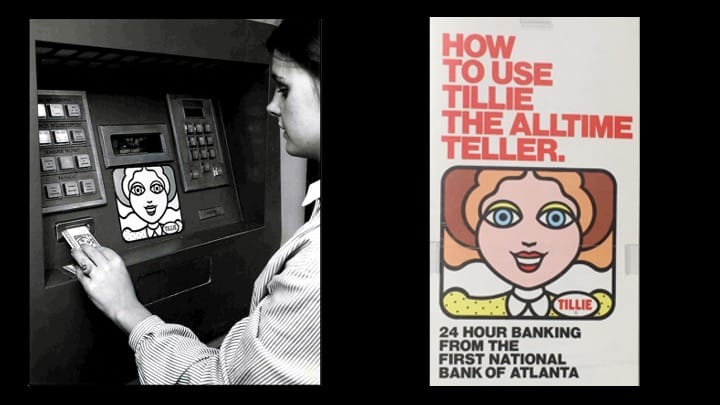

When ATMs became popular in the 1970s, some banks felt it necessary to get their customers comfortable taking cash out of a machine. First National Bank of Atlanta gave its ATMs a face, a voice, and a name: Tillie.

The anthropomorphized cash machine was licensed elsewhere, like American State Bank in Texas, which ran this commercial celebrating Tillie's birthday as though she were just another bank employee:

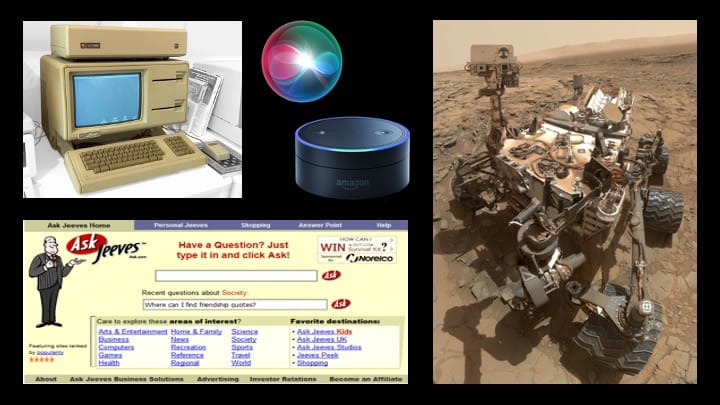

We have a long tradition of dressing up technology in human characteristics, offering analogues to the familiar and putting people at ease with change. Apple's first PC with a graphical user interface, Lisa. The search engine Ask Jeeves. Mars rover Curiosity, seen here "taking a selfie." And, of course, digital assistants like Alexa and Siri. (Fun fact: Susan Bennett, the woman who voiced Tillie the All-Time Teller in ads, went on to provide the original audio files for the voice of Siri.)

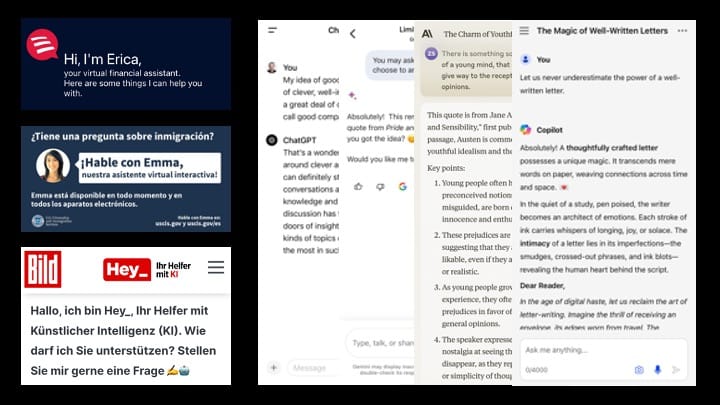

Today people interact with ATMs as the computers they always were, but my bank still wants me to chat with "Erica," the Department of Homeland Security offers immigration advice with "Emma," Europe's largest newspaper greets you, "Ich ben, Hey_," and of course almost every large language model released in the last two years has been introduced to consumers in conversational form.

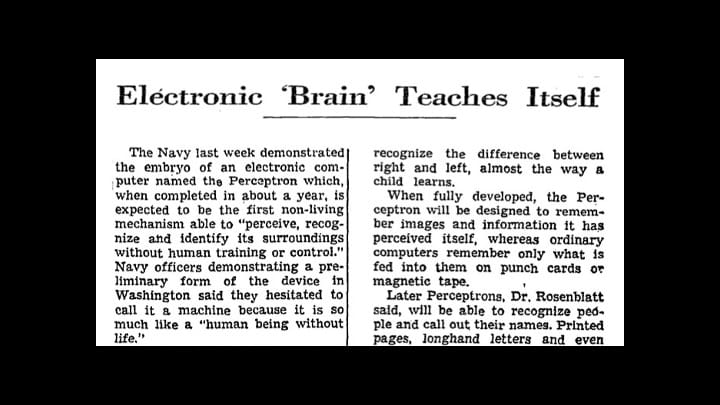

AI is the most anthropomorphized technology in history, starting with the name—intelligence—and plenty of other words thrown around the field: learning, neural, vision, attention, bias, hallucination. These references only make sense to us because they are hallmarks of being human. And it's been that way from the beginning. Here's how The Times, quoting Navy researchers, reported the development of a neural network in 1958:

Aristotle, who had a few things to say about human nature, once declared, "The greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor," but academics studying the personification of tech have long observed that metaphor can just as easily command us. Metaphors shape how we think about a new technology, how we feel about it, what we expect of it, and ultimately how we use it. So it is with AI.

Of course, artificial intelligence is a complex and wide-ranging field of computer science. Unless you feel comfortable hanging out in high-dimensional space, we're going to need some more familiar points of reference. Metaphors can help.

Consider poor Steve Schwartz, whose three decades of distinguished service to the law is now forever overshadowed by his more recent achievement as the first lawyer to get caught using ChatGPT to write a legal brief, inventing several case-law citations in process. I'll admit to having first thought this guy was an idiot. More recently, I've come to sympathize with Steve.

This is what he told the judge, who later fined Steve and his partner $5,000: "I heard about this new site, which I falsely assumed was, like, a super search engine." Super search engine! Where could he possibly have gotten such an idea?

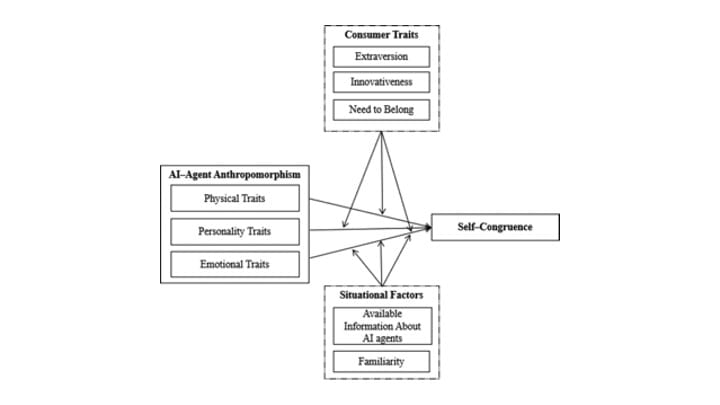

And trusting this super search engine? Well, there's plenty of research showing how humanlike qualities—in this case, a bot that talks just like you do, in a friendly tone, always eager to help—can lead to self-congruence, or seeing yourself in the technology, and thus trusting it more. There's also some evidence to suggest that extroverts, early adopters, and people pleasers are more likely to trust anthropomorphized AI. Steve, in that sense, just wanted to be liked.

That brief was filed more than a year ago. Now, we all know that LLMs are prone to making stuff up—or, in the personifying parlance of contemporary AI, to "hallucinate." Which, of course, implies a sentient being occasionally flipping out.

As a metaphor, it is vivid: You might picture a first-year associate poring over case law long into the night and, after too many doses of speed, hallucinating a few precedents. But as a way of understanding how LLMs work, and how they might work for you, "hallucination" misleads. This is not psychosis, it’s math, probability, predicting the next most likely fragment. It ain't cracking open Westlaw.

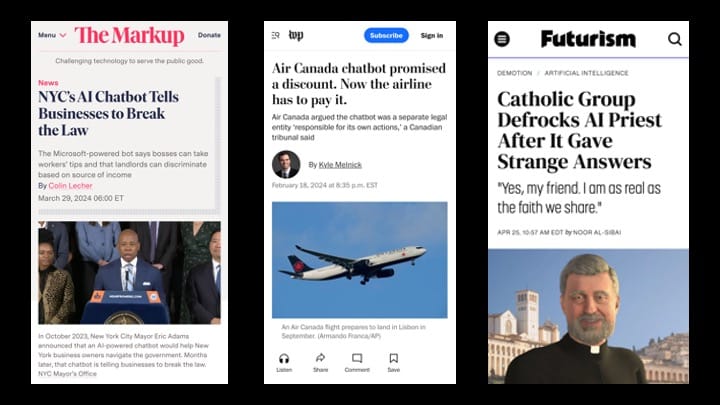

Sure, you can point an LLM at Westlaw and start getting something closer to reliable information. But this obsession with all-knowing oracles has led to over-investment in chatbots that purport to have every answer and inevitably disappoint, or worse, like these recent examples from New York City (which encouraged small-business owners to steal workers' tips), Air Canada (which offered a discount that didn't exist—and had to honor it), and Catholic Answers (whose AI priest encouraged the use of Gatorade for baptisms, among other dubious teachings). AI is not your intern, assistant, or spiritual advisor.

There is something kind of pathological going on here. One of the most exciting advances in computer science ever achieved, with so many promising uses, and we can't think beyond the most obvious, least useful application? What, because we want to see ourselves in this technology?

Meanwhile, we are under-investing in more precise, high-value applications of LLMs that treat generative A.I. models not as people but as tools. A powerful wrench to create sense out of unstructured prose. The glue of an application handling messy, real-word data. Or a drafting table for creative brainstorming, where a little randomness is an asset not a liability. If there's a metaphor to be found in today's AI, you're most likely to find it on a workbench.

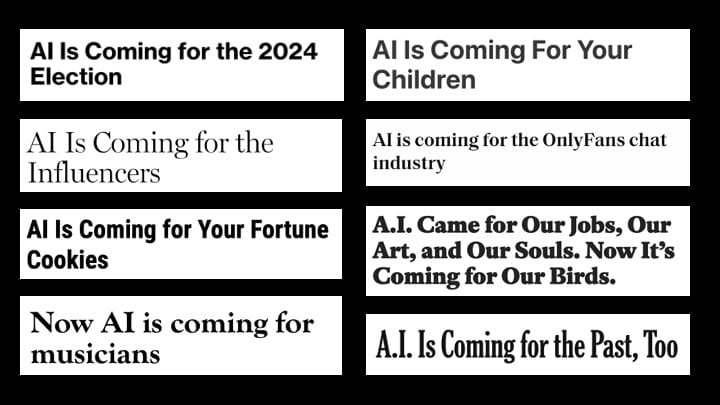

Anthropomorphizing AI not only misleads, but suggests we are on equal footing with, even subservient to, this technology, and there's nothing we can do about it. You see it all the time in headlines that proclaim what AI is "coming for" next: musicians, fortune cookies, your children.

Putting aside the hyperbole, it's also important to remember that AI isn't doing shit. It is not thinking, let alone plotting. It has no aspirations. It isn't even an it so much as a wide-ranging set of methods for pattern recognition and other techniques that imbue software with certain new capabilities, the extent of which we're only beginning to discover. Or, rather, we will begin to discover when we get past these personifying metaphors.

I think this is pretty important, and something I have to remind myself every day, sitting in a newsroom of humans, thinking about how we might apply AI in that context. I keep this image at my desk. It's the cover of a Dutch magazine in 1936, imagining what journalists would look like in the year 2000. Not because this our goal—far from it—but because this is our folly.

A few weeks ago, I was in the midst of drafting our principles for using generative AI in the newsroom, one of those documents I'm sure everyone in this room has labored over. There I was writing the part about the importance of human oversight and accountability—planting a flag for humanity, I thought. Well, someone else took one look at this draft and, with the sharp digital pen of a seasoned editor, made two perfect edits.

Human journalists? Human editors? As if there is any other kind?

Thank you.

Read more from Zach

Sign up to receive occasional emails with new posts.